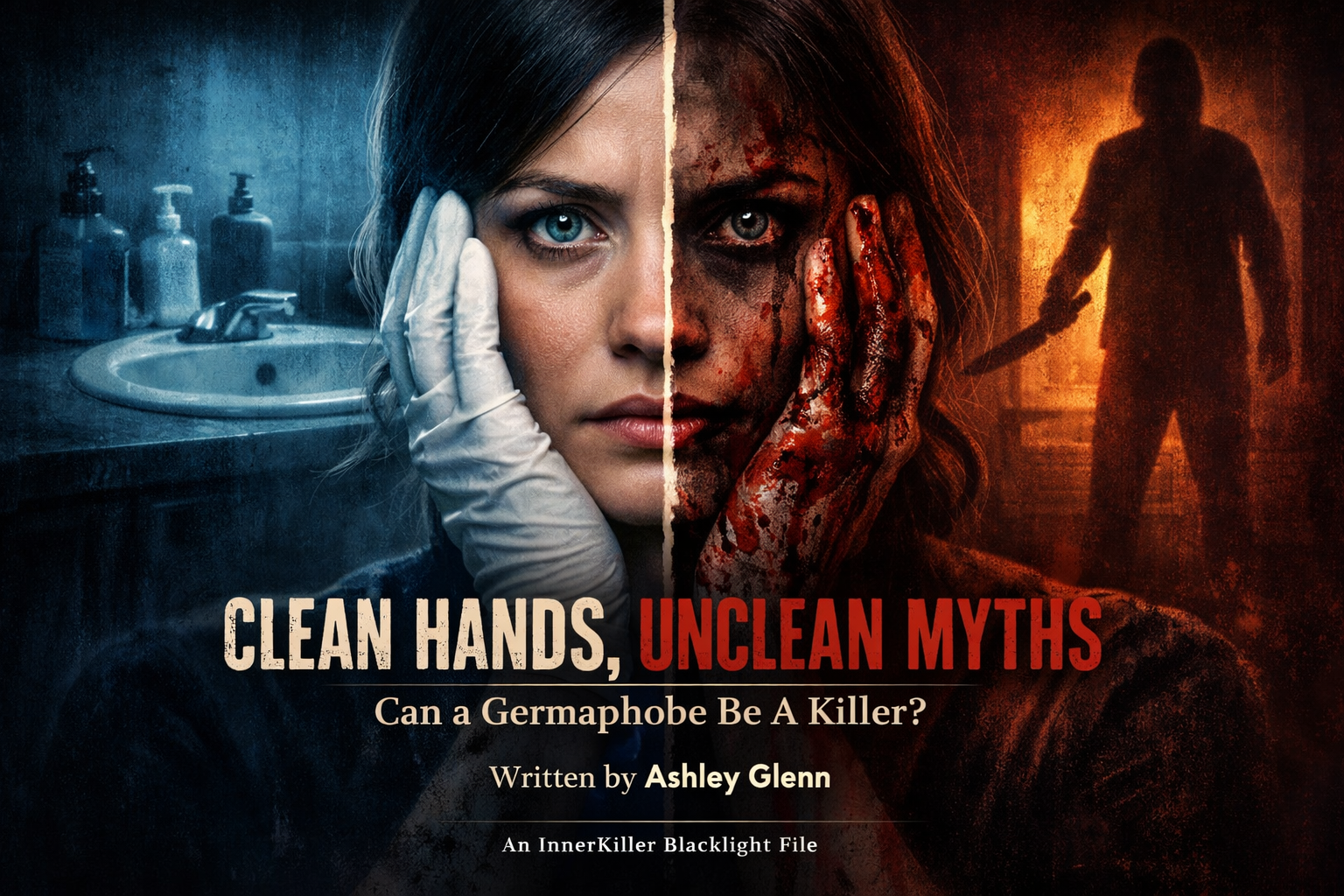

Clean Hands, Unclean Myths: Can a Germaphobe Be A Killer?

The question sounds simple. Almost instinctive.

If someone is deeply afraid of contamination—of dirt, germs, bodily fluids—could they really be capable of killing another person?

The assumption beneath the question is that disgust and violence are opposites. That fear of physical impurity implies reverence for life. That meticulous cleanliness equals moral restraint. It is an understandable leap—but it is also a cultural shortcut, not a psychological truth.

To understand why, we need to separate what a fear protects against from what a conscience protects against. They are not the same system.

Germ Aversion Is About Threat, Not Ethics

Germaphobia—more accurately described as contamination-focused anxiety—centers on perceived threat to the self. The threat may be illness, loss of control, or an overwhelming sense of internal violation. What matters psychologically is not cleanliness itself, but the regulation of fear.

This type of anxiety does not originate from a moral compass. It originates from a nervous system seeking safety.

A person can be intensely avoidant of dirt and bodily contact while holding no particular ethical stance about harm to others. Conversely, someone can tolerate mess, blood, or physical chaos while maintaining strong moral prohibitions against violence. These traits operate on different tracks.

Fear is not a value. It is a response.

The Myth of Cleanliness as Character

Culturally, cleanliness has long been associated with virtue. Language reflects this: clean hands, dirty deeds, stained conscience. These metaphors are powerful, but they blur psychological reality.

When we encounter someone meticulous, hygienic, or visibly uncomfortable with contamination, we often infer softness, sensitivity, or harmlessness. This inference is emotional, not evidentiary.

History—and clinical observation—offer no support for the idea that fear of germs inoculates someone against cruelty, coercion, or even lethal violence. What it may do instead is shape how a person manages proximity, control, and exposure.

Control Can Wear Many Masks

Anxiety thrives on predictability. So does power.

For some individuals, strict routines around cleanliness are not just about avoiding illness; they are about mastering uncertainty. The same drive can, in different contexts, express itself as emotional detachment, compartmentalization, or rigid boundary enforcement.

This does not mean germ aversion causes violence. It means that both anxiety and harm can coexist within the same psychological architecture without cancelling each other out.

One does not negate the other. They simply answer different internal demands.

Avoidance Does Not Equal Aversion to Harm

Another misconception is that disgust toward bodily fluids implies an inability to engage in physical harm. This confuses sensory aversion with moral inhibition.

A person may find blood deeply distressing—and still believe another human being deserves punishment, erasure, or removal. Distance, tools, delegation, or dissociation can bridge the gap between aversion and action without ever confronting the feared stimulus directly.

Violence is not always intimate. It is not always chaotic. And it is not always incompatible with avoidance.

Why This Question Persists

We ask whether a germaphobe could be a killer because we want reassurance. We want clean lines between danger and safety, between “people like that” and “people like us.”

If fear looks familiar, we feel safer.

If discomfort resembles our own, we assume shared values.

But psychology does not organize itself around our comfort. It organizes itself around survival, coping, and adaptation—sometimes in ways that contradict our narratives about goodness.

Curiosity Without Collapse

Exploring questions like this does not mean suspecting people with anxiety. It does not mean pathologizing cleanliness or turning fear into a warning sign.

It means resisting the urge to turn traits into shorthand for character.

Germ aversion is not a moral shield.

Neither is it a marker of danger.

It is simply one way the human nervous system responds to perceived threat.

Closing Reflection

The danger lies not in asking whether opposites can coexist, but in believing they cannot. When we rely on surface traits to tell us who is safe or unsafe, we trade understanding for illusion.

Under steady light, the picture is quieter—and more unsettling. Fear does not guarantee mercy. Order does not equal ethics. And human behavior cannot be disinfected into something predictable.

What protects us is not assuming who would never do harm—but learning how easily our assumptions can fail.