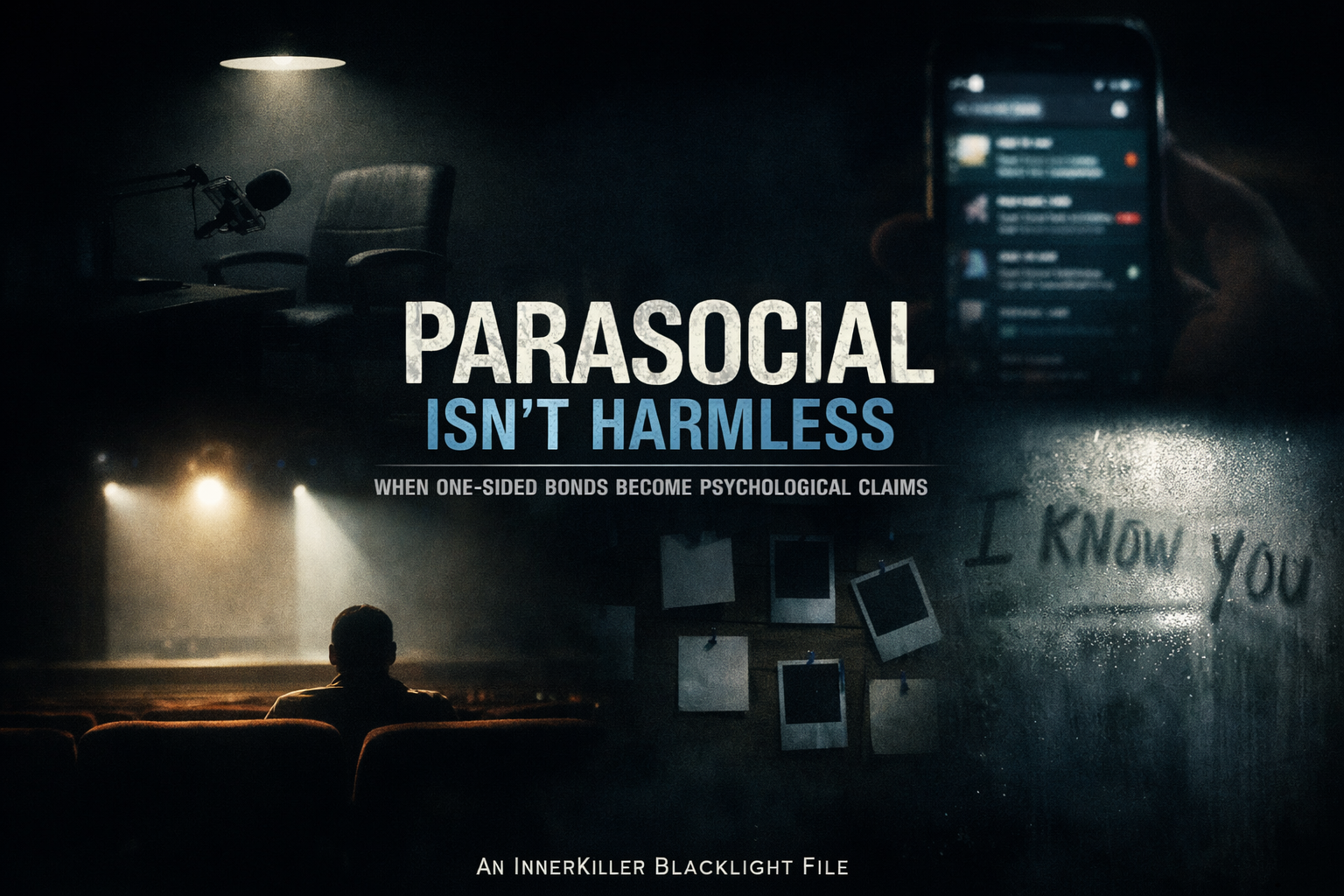

Parasocial Isn’t Harmless: When One-Sided Bonds Become Psychological Claims

Parasocial relationships rarely announce themselves as dangerous.

They begin quietly—through screens, voices, characters, or public personas—forming in spaces where access feels intimate but remains unreciprocated. For most people, these bonds stay where they begin: as admiration, comfort, or identification. But the structure itself carries risk when mistaken for mutuality.

A parasocial bond is, by definition, one-sided. The viewer, listener, or reader experiences emotional familiarity, while the subject remains unaware of the individual experiencing it. This asymmetry is not a flaw; it is the condition. Problems arise not from the bond’s existence, but from how it is interpreted.

Culturally, we normalize parasocial language.

We say a creator “feels like a friend.” We describe public figures as “relatable,” “authentic,” or “someone who gets me.” These phrases are shorthand for resonance, not access. Yet resonance can blur into perceived intimacy—especially when media environments reward disclosure and proximity.

Psychologically, the brain is efficient, not precise.

Repeated exposure builds familiarity; familiarity can generate emotional safety. When someone speaks directly to a camera, shares vulnerability, or narrates personal experience, the viewer’s nervous system may register connection even without reciprocity. This is not delusion—it is human patterning responding to mediated cues.

The ethical fault line appears when internal experience becomes an external claim.

“They feel like they know me” is an internal state.

“They owe me acknowledgment” is a boundary crossing.

This shift does not require malice. It can emerge from loneliness, identity formation, or unmet relational needs—particularly in periods of stress or transition. But intent does not determine impact. When perceived intimacy hardens into expectation, entitlement, or pursuit, harm becomes possible.

It is important to distinguish parasocial attachment from pathology.

Most parasocial bonds never escalate. They dissolve naturally as interests change or life expands. The danger lies in misreading the bond as reciprocal—or as justification for contact that bypasses consent.

Digital environments complicate this further. Platforms collapse distance: comments, direct messages, live interactions. Visibility can be mistaken for access; response for relationship. The architecture itself encourages misinterpretation, especially when attention is intermittent or selectively reinforced.

From a safety perspective, the concern is not fandom—it is boundary erosion.

When internal narratives override explicit limits, when imagined closeness dismisses real-world autonomy, when disappointment converts into grievance, the bond has shifted from observation to claim. At that point, the issue is no longer interest—it is entitlement.

For creators, public figures, and professionals, this dynamic carries moral weight. Disclosure invites resonance, but it also demands clarity. Ethical engagement does not mean withholding humanity; it means maintaining visible boundaries that protect both sides of the interaction.

For audiences, literacy matters just as much. Recognizing the difference between emotional impact and relational access is a protective skill. Feeling understood does not mean being known. Being moved does not imply being invited.

This is not an argument against connection. It is an argument for accuracy.

Parasocial relationships reveal how easily the mind fills gaps—how stories, voices, and images can feel personal without being interpersonal. Under steady light, the risk is not fascination itself, but confusion about where it belongs.

Understanding that distinction is not about suspicion or shame.

It is about preserving autonomy—yours and theirs—before imagination begins to overwrite reality.

Under Blacklight, clarity is not punitive. It is protective.